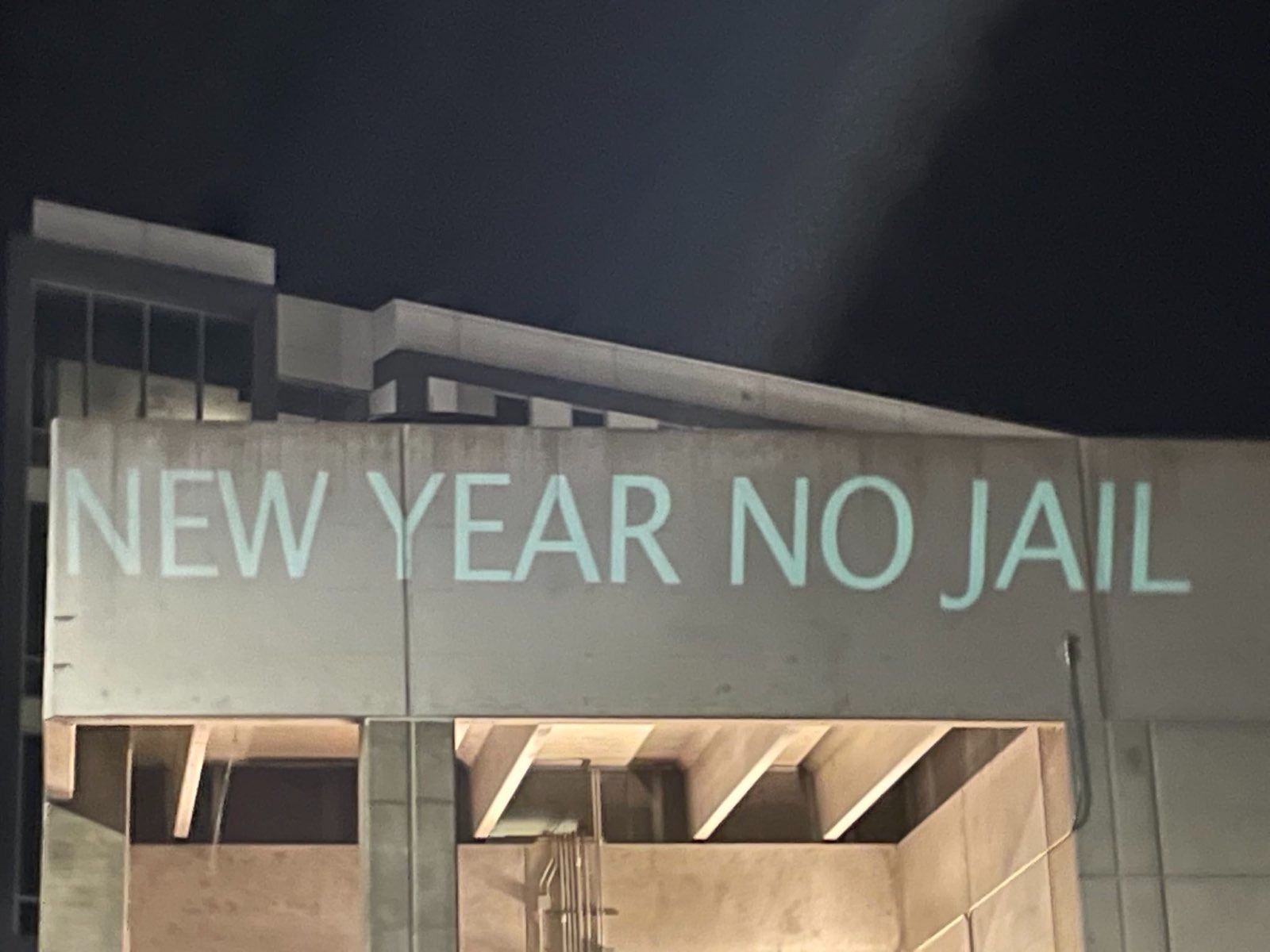

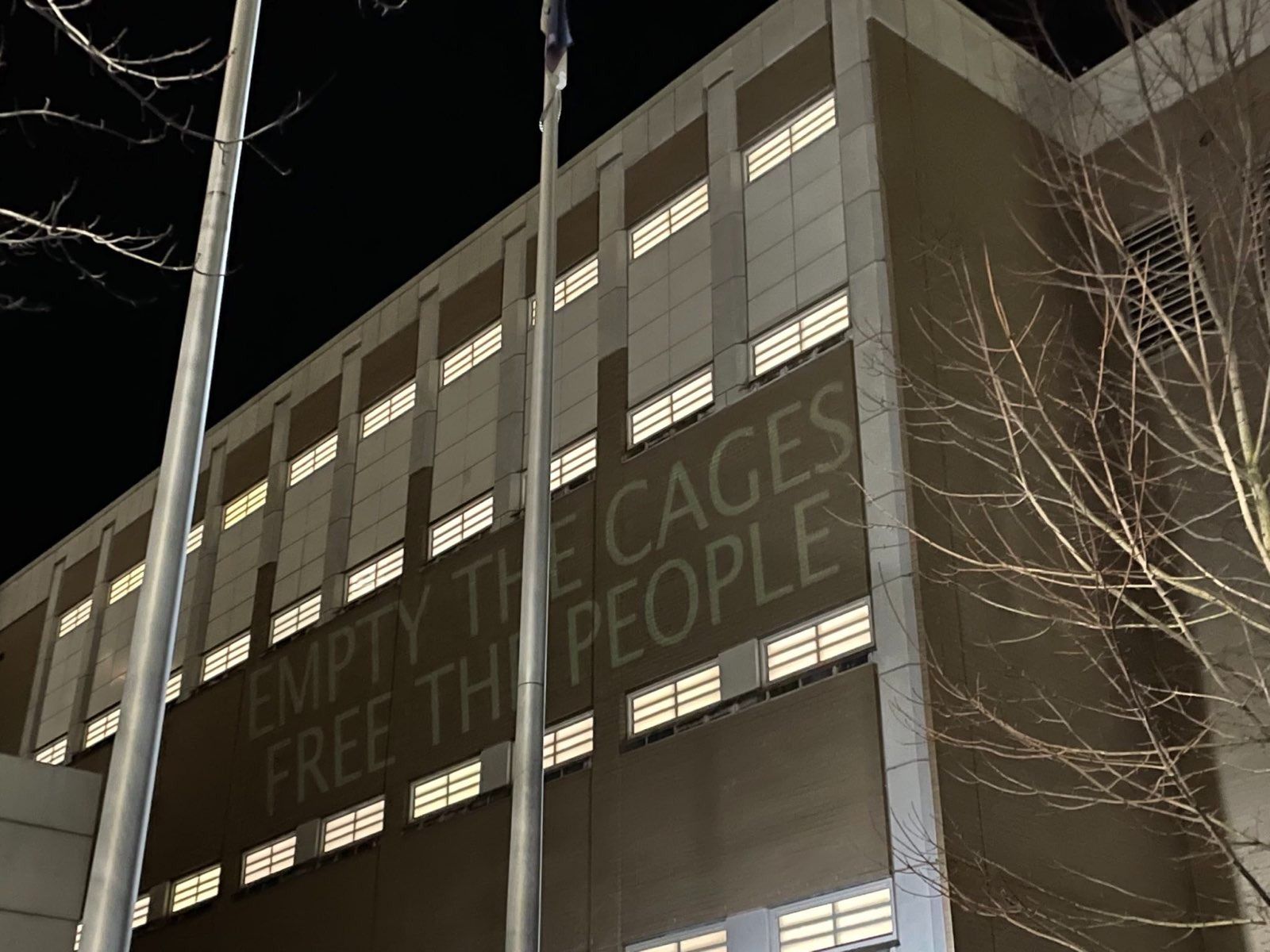

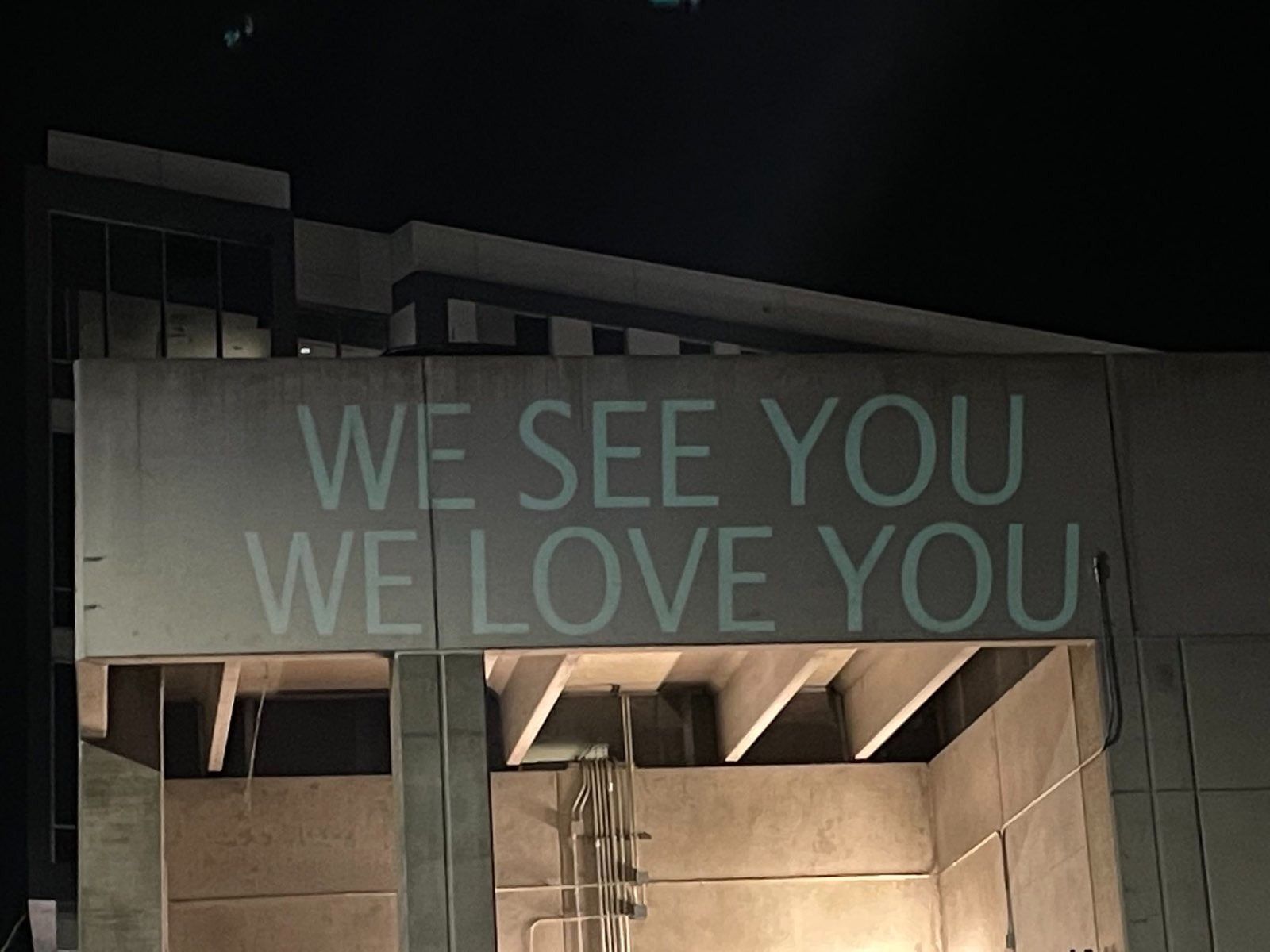

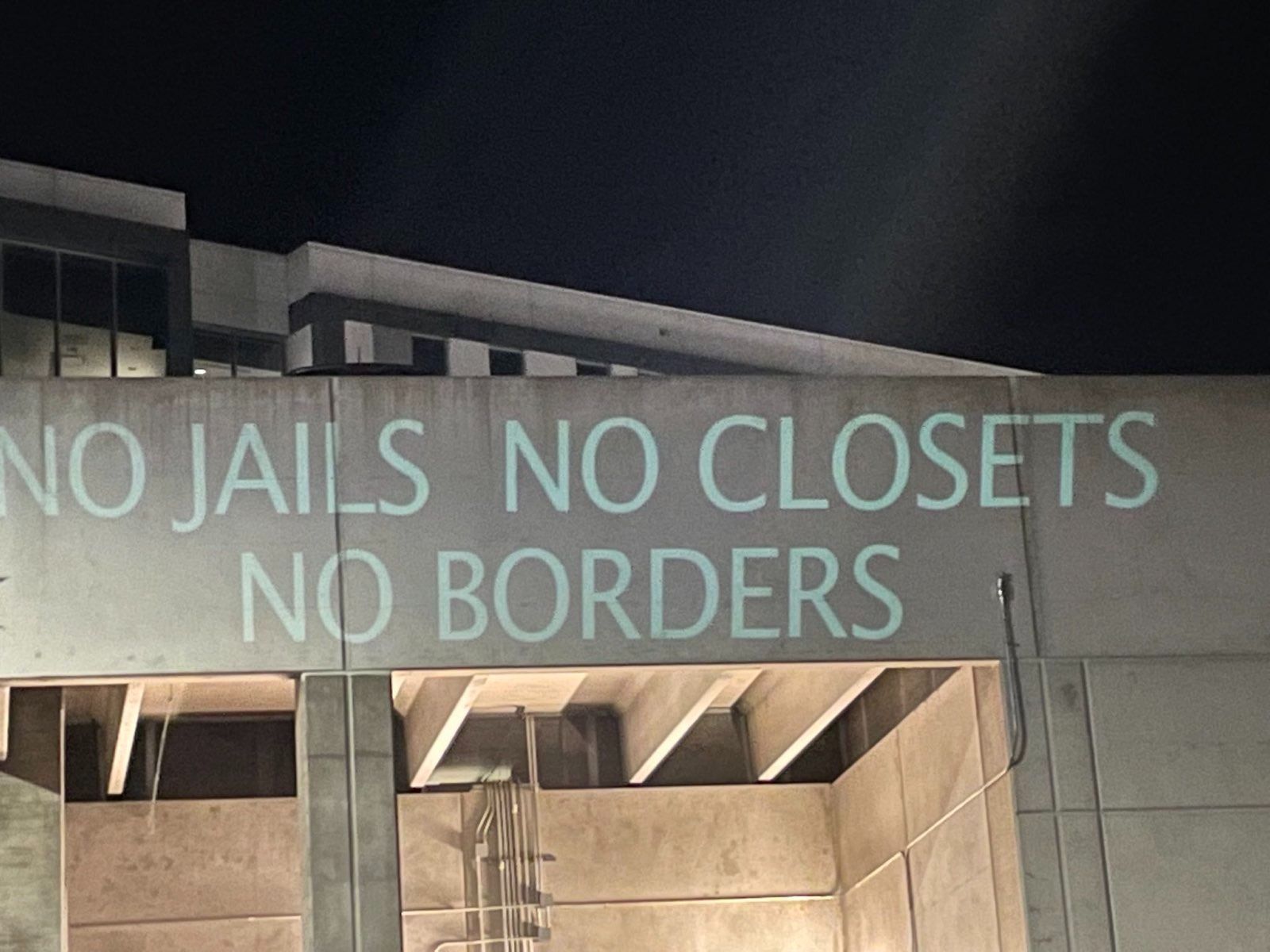

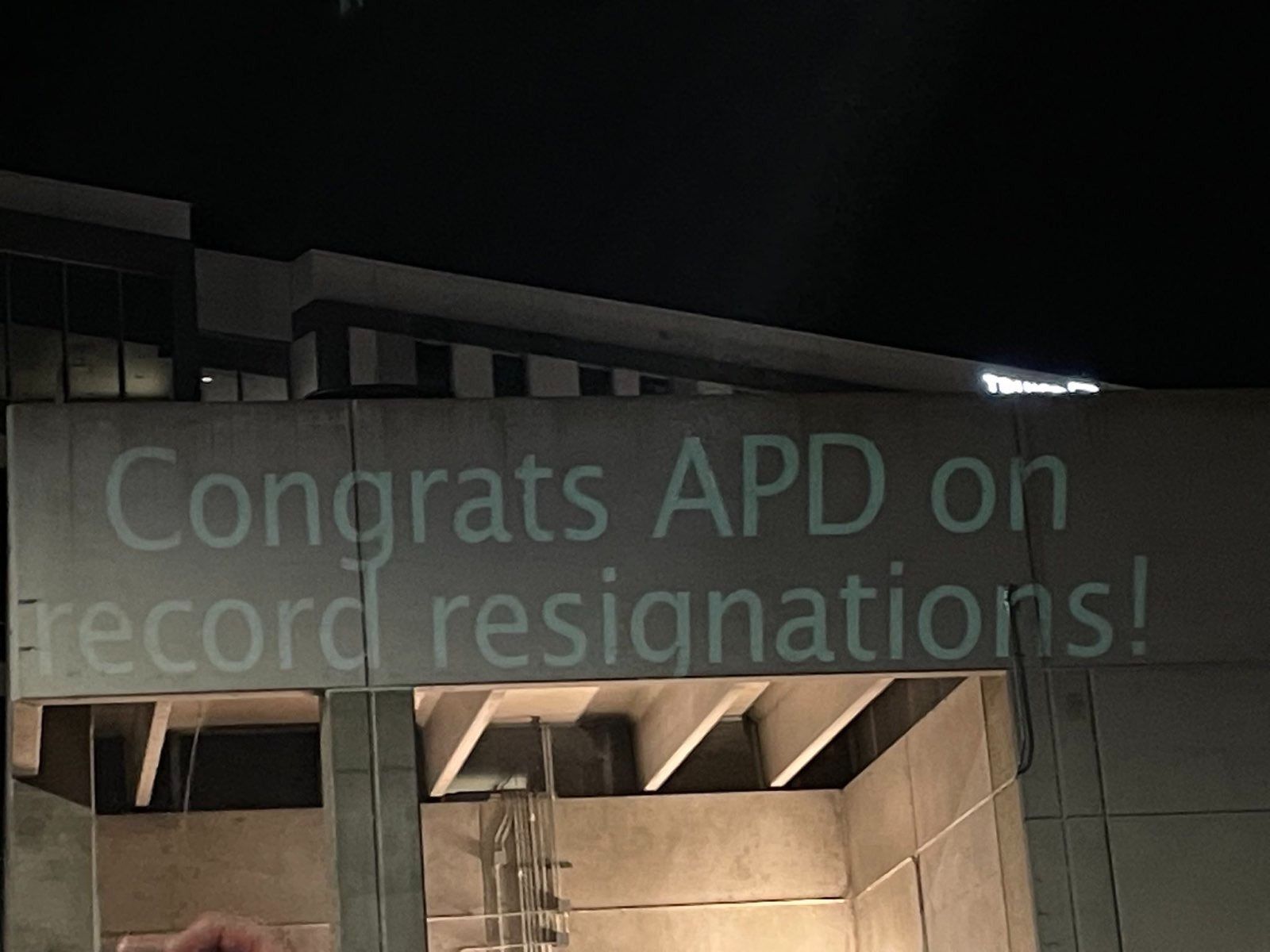

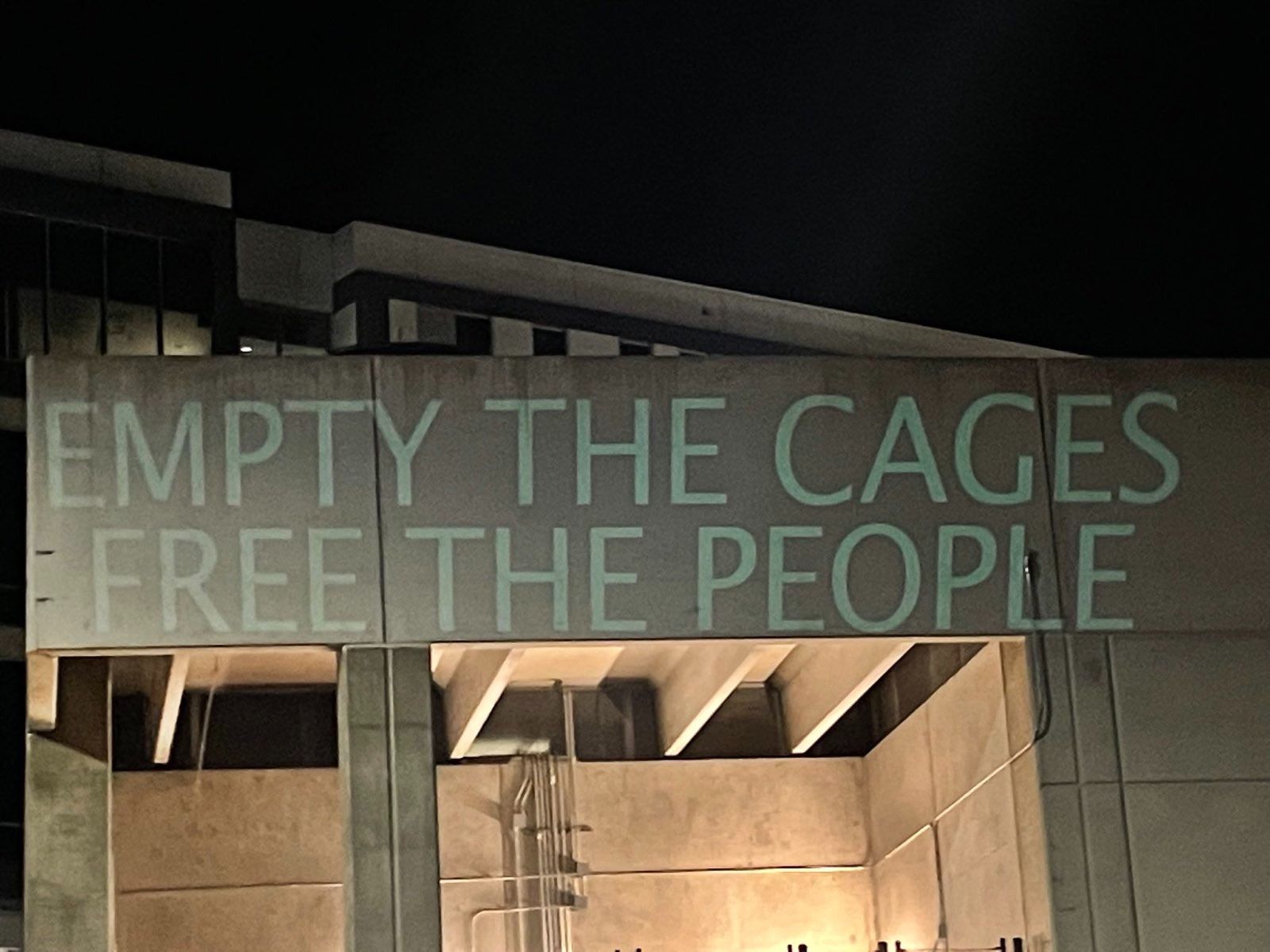

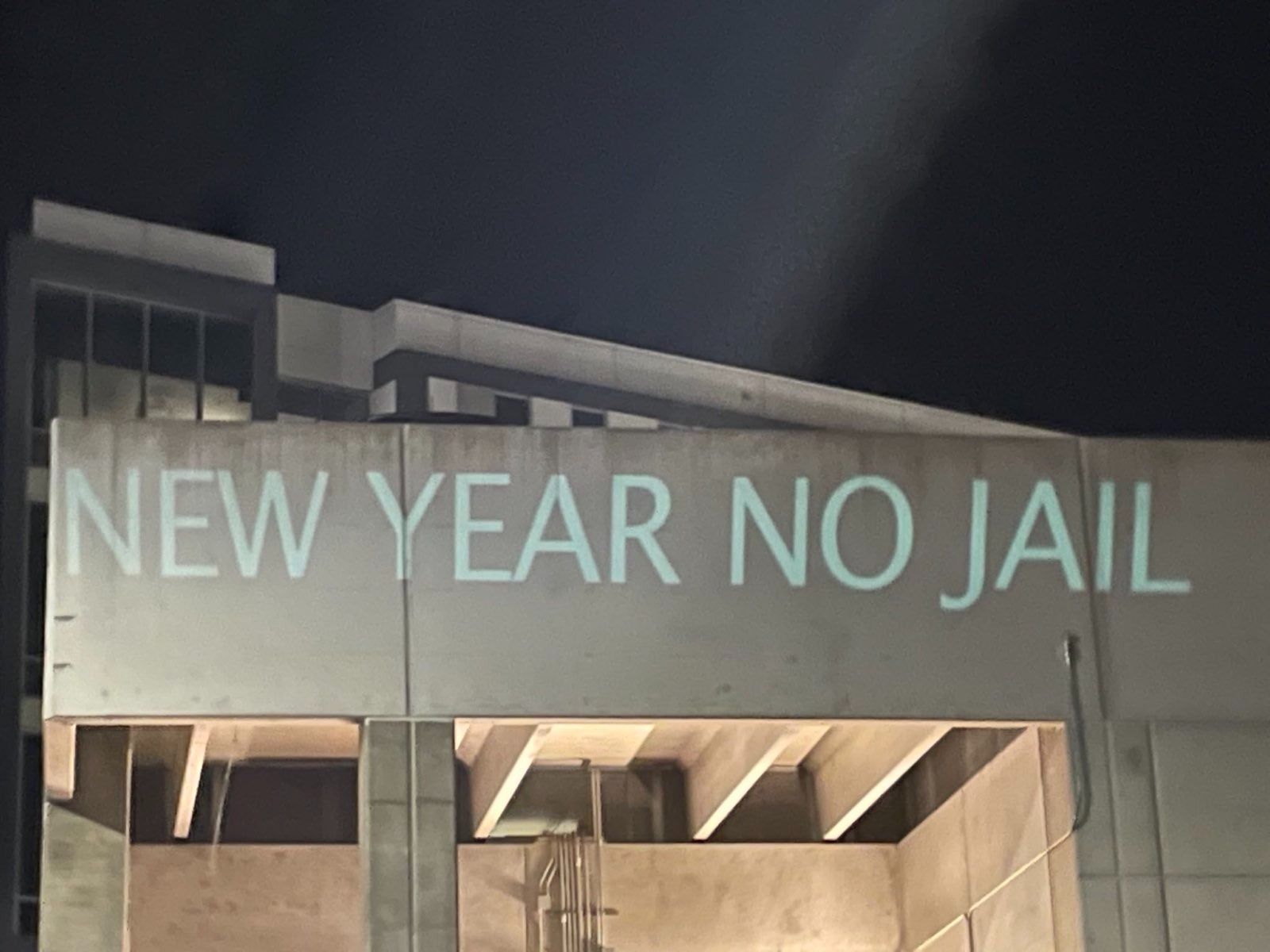

On December 31st, 2021, approximately eighty locals gathered outside of the Buncombe County Detention Center to project messages on the walls where incarcerated people could see them, bang on pots and pans, shout chants, blow air horns, shake noisemakers, and generally make as much sound as possible.

This annual tradition – called a New Year's Eve Noise Demonstration, or "NYE Noise Demo" for short – has been organized in Asheville since at least 2016. The tradition appears to have started in Greece around 2008, but its origins have a distinct "folk tradition" haziness which precludes a full genealogy, even among people who have been organizing the event for a decade.

In 2010, a group called the North American Anarchist Network put out a global call to action for solidarity with incarcerated individuals, and in the 11 years since many U.S. cities have answered the call. Other U.S. cities where confirmed Noise Demos occurred this New Year's Eve include Tucson, AZ, Waupun, WI, Cleveland, OH, Fort Lauderdale, FL, Atlanta, GA, Richmond, VA, Worcester, MA, and New York City, NY.

This year in Asheville, organizers also launched a "Community Bail Fund" and managed to bail out nine individuals as part of the demonstration.

We spoke with local organizers Ash Williams and R about the Noise Demo, its purpose, and its context in Asheville. We also spoke with Julie, an organizer with the Asheville Community Bail Fund about the new project. Find those interviews below.

What is a New Years' Eve Noise Demonstration? What typically happens at these events, and what happened in Asheville this year?

Ash: "So, in my experience, noise demos are a tool that abolitionists and freedom fighters have used to connect people on the inside and outside for a really long time.... And so, if you can imagine a noisy demonstration on New Year's Eve, you know that like – we hold space for community folks on the outside to connect through noise with people on the inside. And so it's a really beautiful kind of loud, moving action that involves yelling, and music, and screaming, chanting, and overall just trying to connect."

R: "I would say that noise demos outside of jails and prisons are a long standing anarchist [and abolitionist] tradition. People go and show solidarity and advocate for abolitionist practices by really just showing up and making a lot of noise to let people who are on the inside know that people care about them and see what is happening.

In Asheville, I think that it's been going on for about five years. And so, the tradition has been, you know, earlier in the evening on New Year's Eve for people to meet up near the downtown detention center and bring bucket drums and whatever else people have – pots and pans – to bang together. We'll be outside the jail in whatever capacity we can be. And then it ends well before midnight, probably around 9 or 10 p.m. usually, and people go on to do their other little New Year's Eve things. It wasn't until last year, in 2020, that we started trying to bail people out on New Year's Eve as well....

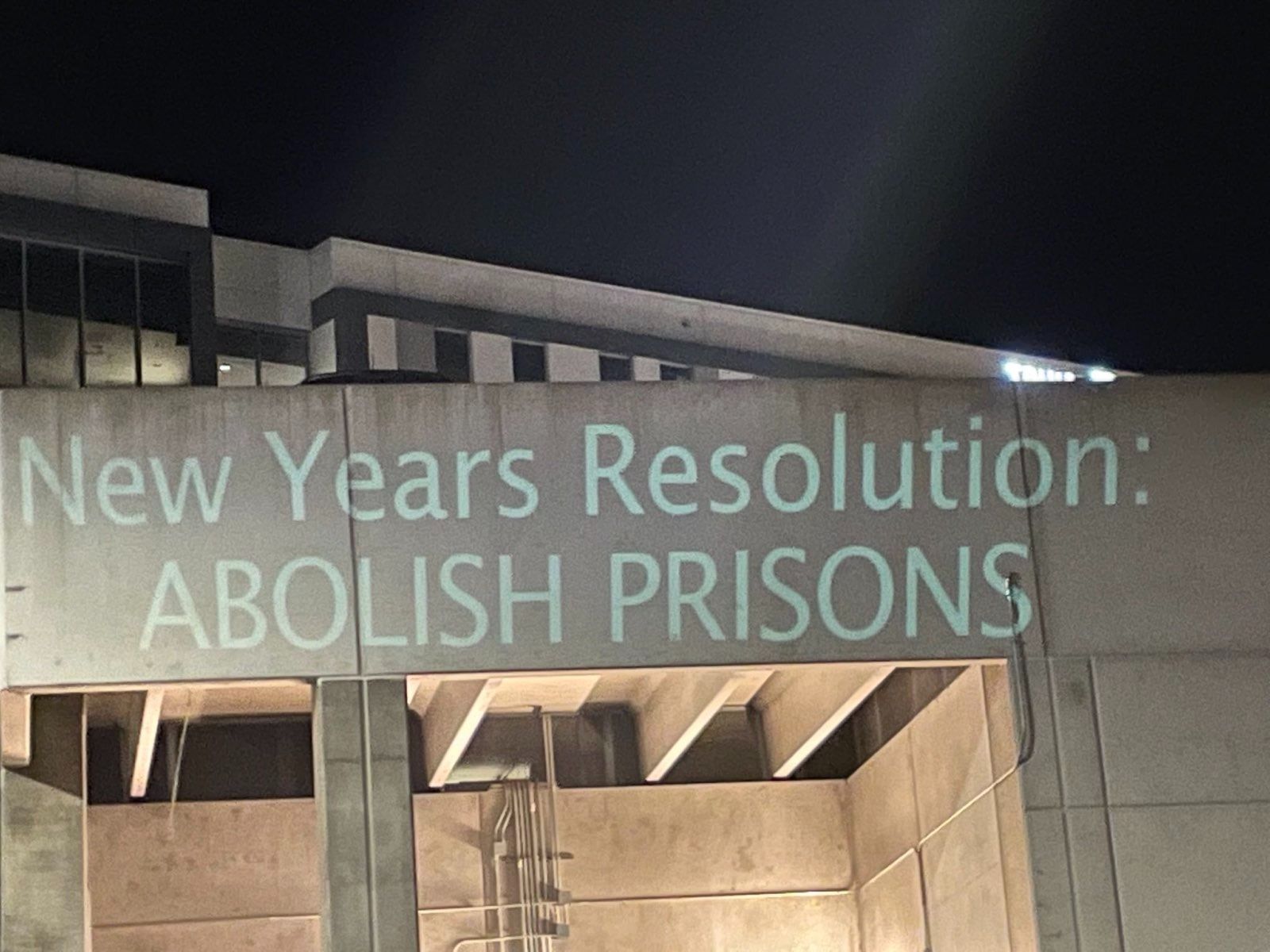

Even though the Community Bail Fund wasn't a publicly launched project last year, the same people who did the work to bail people this year did the same thing last year, and I think we got three people out just off of money that was raised. And, you know, that just adds another level to the work that we're trying to do, and we're trying to say that no one should be in jail ever, we believe. If we're going to set a New Year's resolution, it needs to be an abolitionist one. So, we're trying to get as many people as possible out and we're trying to send a very clear message that 'we're not here for prisons.'"

What is the purpose and goal of this demonstration?

Ash: "Historically, and in the south, I've seen noise demos take place on New Year's Eve as a way to amplify the lived realities of those who are inside, and to also create a space for connection for those outside. I really like noise demonstrations because I believe in using noise as a practice. I think that is what abolition calls us to do – as a Black person, I think that's what Black organizing calls us to do. And I think really cool things happen when we use noise to disrupt systems of oppression, but also like physical spaces...

One of the things I like to say, I think I started the noise demo off with saying this, is 'I don't know about y'all, but all throughout the year, we've been doing these call-ins, and it's been COVID, so we're doing a lot of virtual shit. We're emailing, we are showing up for folks in our communities, but the noise demos are for us to like, turn up and get loud and get angry or show the range of other emotions that you can feel about the fucking jail' and so on... We might, you know, come downtown or pass the jail or be around the jail and not remember, recall that there were people in there. And so a lot of the things I was saying on the mic was to remind folks that we might drive down here and act like we don't see these folks, but we know they're here.... As an abolitionist, I know that the jail is meant to disappear people, not just to remove them from their communities. So it's really important that we make those connections for folks while we're out there, too. And so I also hope that the New Year's Eve noise demonstration serves as just another tool that folks have to use against jails and the police."

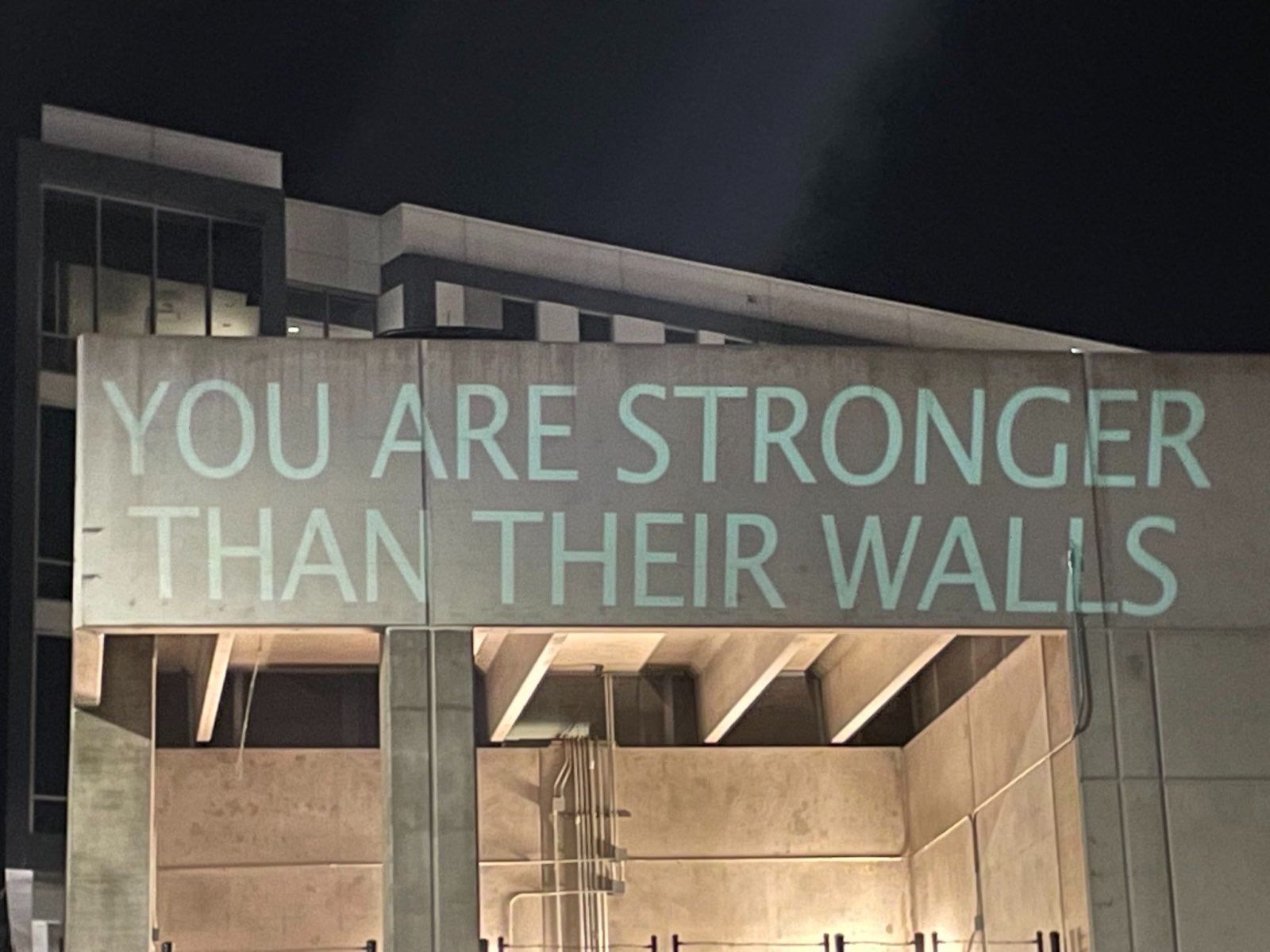

R: "I think that the purpose is to break down the barrier, the walls that feel so alienating between us and the people on the inside... It is a way to let people on the inside know that there is a group of people on the outside, too, that care about them, are like them, and are there are with them, you know? Like, literally there with them. And even though we're separated by this really violent institution, we can still show up, we can still make noise. We can still demonstrate through noise that we are there. That's what feels valuable to me.

And I can't speak for other cities. But in Asheville, almost every year that we've done it, it's not just a party on the outside, it's a party on the inside, too. People start flashing their lights on the inside, they'll start waving. People will be, you know, kind of partying with us. And it does feel like a moment of true connection that transcends the cages. And even more so as we're bailing people out, you know, this year, it felt really special. Someone was able to get bailed out by their sister and was able to come outside as people were outside banging and clanging and was able to join us! It was a really sweet moment.

But I think [the purpose is] to just really make some noise and it also feels like there's just an element of disruption to that. I have a lot of admiration for actions and movements that are centered around showing up and making some noise, showing up and causing a disruption, showing up and saying, 'Hey! We're here, and we're not down with what's going on!' And I think that there's something really valuable to that disruption... jails are disruptive. So why not?"

Have you received any feedback from incarcerated people? How are they communicating with you, and what do they have to say?

Ash: "So, this is my second year participating in the noise demonstration in Asheville. I met someone, actually, at a park raid – a time when the police were raiding a park – this was someone who had gotten out of jail but was in there during the last noise demonstration... They let us know that on that night they could hear us, and they remember the noise demonstration from that year.

One of the things that I'm always looking for as an organizer is some kind of response, if you will, from those inside. And so the responses that we get from folks inside [can] look like them using things to flash their lights... or, this year, we used fireworks to communicate with folks. That was really beautiful to see. Folks also did other things, like sometimes they put messages in the window, or they wave as much as they can as we are making noise on each side of the jail. And so it's a really beautiful sight to see, especially in the dark."

R: "Yeah, actually, we met someone in the past year. We met someone who was locked up in the county detention center last year during New Year's, who heard us and saw us and knew what was going on... [they were] able to say, 'Oh y'all, were the people doing the New Year's thing? I remember, y'all! I heard you!' And that was a really cool. It was a cool moment to just be able to say... we know people can hear it because they're flashing their lights and waving and hanging out, but to actually have a conversation with someone where they were like, 'Oh, those are the New Year's people!' That was so great. The feedback that we've gotten is really positive, especially bailing people out."

Can you speak about the context surrounding this event in Asheville? Are there any reasons the event holds special significance here?

Ash: "The majority of the organizing that I have done in my life has primarily been in Charlotte [NC], especially around the jail and around jail deaths. And so moving here, it was really important for me to connect with the people who gave a fuck about the people in the jail here. And as I understand it... four people died in the jail here in 2021. That is alarming to me. I hope that that is alarming to everyone, right? Coming from Charlotte, there were a lot of jail deaths in the last five years... and knowing what the context for the jails look like in Charlotte, Durham, and now in Asheville, I would say jail deaths are increasing.

You know, sometimes people go inside of Buncombe County Detention Center and they do not come out. And so for me, it's like, we don't send anyone there who we care about! We don't send people there who we don't even care about because, yeah, the jail facilitates people to death. And so that's one of the other things that I think is really important to name about the action.

This year, I think... people are paying attention to things like gentrification and powerlessness, anti-Black racism, and police violence. And I think that, you know, it's easy to think that those things are mutually exclusive. But I think the New Year's Eve noise demonstration allows us to really bring a lot of different issues together because... you know, at this particular action, there are folks who were bailed out that day. So we got to see what that demonstrating looks like, kind of to the Nth degree of like... getting someone out of jail. So we're making noise, but we're also bailing people out because we take that urgency of people being inside so seriously. And also, we're not forgetting those [four] people who died in the Buncombe County Detention Center last year."

R: "I think in the face of so many people being downtown on New Year's Eve who are tourists... who are here as perpetuators of the prison industrial complex by way of giving money to hotels and a tourist industry that is actively invested in keeping people out, and policing homelessness, in order to perpetuate this kind of tourism safe haven... to have a presence downtown that is, you know, celebratory in a New Year's fashion, but really kind of... forcing people's attention towards the jail that they're partying around, the jail that gets washed over when you're downtown at breweries, or whatever. People don't want to acknowledge the fact that there are [incarcerated] people right next to where they are drinking and having fun. And so, yeah, I think that... engaging in the New Year's partying energy, but shifting the focus away from tourism and towards abolition in Asheville specifically is very important. There's a lot of policing, there's a lot of violence that goes into making Ashville a place for tourism. So yeah, I think that that's why it's important in that moment in this place."

Is There Anything Else You'd Like to Share?

Ash: "As conditions change for the folks on the outside regarding COVID, I hope that people are also paying attention to what's happening with folks who are inside the Buncombe County Detention Center as a result, as it relates to COVID Omicron. Things are changing every day. There's a lot of misinformation. I am constantly thinking about folks inside of all places of incarceration, but especially where I live, you know? And so I care about whether or not folks have access to masks and testing and vaccinations. And yeah, that's something that's just really on my mind lately. You know, these places... they can't keep anyone safe, but that's another reason why they just need to let everyone out of there."

R: "I want to say that I'm really grateful. I'm really grateful for everyone who comes out. I'm really grateful for everyone who participates. Something that I always say every year is that hopefully next year, we don't have to do this action again because hopefully next year jails will be obsolete. And until that's true, we're going to keep doing it."

See the interview with Julie of Asheville Community Bail Fund below the image gallery.

What is a Community Bail Fund? Can you describe this project?

Julie, Asheville Community Bail Fund: "A community bail fund could be many different things because different people with different goals, political commitments, values, and access to resources and relationships do community bail funds. So, I guess they're not monolithic... but the general idea of a bail fund is one in which funds are raised and held so that when people are arrested, they can call that bail fund for assistance with getting bailed out...

Then, if that person chooses to return to court to wind their way through the criminal justice system – if they do that and go to all their court dates and stuff, that money actually comes back to the bail fund. That's why you'll sometimes hear it called a 'revolving bail fund.'

Some bail funds are really huge, or are nonprofits, or are grant-funded, or have access to private donations and things like that. They can run up to millions of dollars. Then, some are obviously smaller and more grassroots, and I think I would categorize ours as the latter – at least, you know, for now.

Another thing that is important to note is that – you know, this is the beginning of the project, so things are still taking shape, but as of right now we don't make distinctions between people with particular charges. So like, some bail funds will only bail folks out of a particular identity, or particular charges like 'non-violent drug offenses' or something like that. We don't do that, so that's one of the features of our bail fund.

We will also provide reminders or rides to court if the person wants it. We bailed nine people out over New Years' and a couple of people wanted that kind of follow-up, so we'll do that kind of post-release support if they want to engage with the criminal justice system...

Ideally, I think, we want to be building relationships and be part of movement ecosystem that is working in the shorter term towards the end of cash bail, and in the longer term towards a world without police or prisons."

Why is bail support important?

Julie: "We have a cash bail system in the United States – we're one of only several countries that have a cash bail system, it's not that common – and it's a really exploitative system, where you're basically holding people for ransom, pre-trial, solely on the basis of the fact that they don't have money. So, a person who catches the same charges – if they have money, they can pay that ransom, and get out of jail, and be able to fight their case from the comfort of their own home, if they're lucky enough to have a home. Someone who doesn't have access to financial resources has to stay in jail pre-trial, which, among other things, can have so many collateral consequences that make that person's circumstances even more unstable. They could lose housing... sometimes, terribly, they could lose their children... so, all kinds of collateral consequences from sitting in jail while waiting for a trial to happen.

This is also a driver of coercive plea bargaining. The state knows that people don't have money and don't want to sit in jail, so here comes the DA with a plea bargain that's going to look good to you when you've been sitting in jail for three months or six months, or a year.

There's data that shows that people who have to fight their case from inside a jail cell have way worse outcomes for their cases, too.

So, for all these reasons – in addition to just, like, general human ethics – the cash bail system is terrible and predatory...

At this time, we don't work with bail bondspeople, so we don't hire private bail bonds that charge 10% for posting bail... right now, most of the time, the way someone gets bailed out is like: If the bail is $5,000, the person pays 10%, which is $500, of that to a bondsperson who will then go post bail, and keep the $500, and then when that person goes to court, the bondsperson gets their $5k back while skimming the 10% off the top. So, we're not doing that – we're actually doing an endrun around those kinds of folks."

I remember seeing an "Asheville Jail Support" during the summer 2020 protests – is the bail fund different? If so, how?

Julie: "Asheville Jail Support worked with an activist bail fund that has existed in town for several years, and was always pretty small. During the uprisings in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and so many others, that bail fund just got an influx of donations, which were used, but after the reality of multiple people being arrested every night ceased, that small activist bail fund did not need the amount of cash that had come in. This is important, because it speaks to the roots of the Asheville Community Bail Fund... there was an understanding that in addition to an activist bail fund that exists in order to be a support for people who are engaging in protests, or activism, dissidence, resistance – whatever you want to call it – there is also a need to support folks who are getting arrested for non-protest activity... because they are also under attack.

The ways in which people in the community in general are under attack has been increasing and intensifying as we see an intensification of what I would call 'multiple overlapping structural crises.' Whether that is the pandemic, gentrification, affordable housing crisis, opioid crisis... the state has decided to respond to these overlapping structural crises with a program of criminalization, and with a program of removal, and disposal. So, that is the state's response, that is the City of Asheville's response, that is Buncombe County's response, to these overlapping structural crises... and that results in lots of people getting locked up.

So... it was the two factors, the intensification of this program of criminalization against poor people and people of color, with the reality of more resources coming into the existing [activist] bail fund that allowed the folks behind the Asheville Community Bail Fund to spin that off. [The Asheville Community Bail Fund] was basically gifted money from the activist bail fund to seed the new fund. So there is a direct relationship, but they are not the same.

And again, Asheville Jail Support was just a group who was working with that activist bail fund... folks working with Asheville Jail Support didn't work with just anyone at the jail, all the time, around the clock... that was infrastructure that was just put in place for the protests."

Asheville Community Bail Fund got nine people out on New Years' Eve – how were these people chosen? What did they have to say about the project?

Julie: "So, this is perhaps a little bit misleading because we kicked off the [Asheville Community] Bail Fund on New Year's [Eve] wanting to bail folks out, but that's not actually how the bail fund is going to function ongoing.

So, for New Year's [Eve], we were like, 'we have this money and we want to use it to get some folks out,' so we just basically went through a list of folks who were in the jail, and based on a number of factors including how much money we had, how long folks had been in, and how much their bail was – as well as some demographic considerations, like we tend to try to prioritize people of color or people who have marginalized identities that might make them more vulnerable, you know, gleaning whatever we can from the [Buncombe County Jail] website – based on that combination of factors we identified nine people who we could get out. It's actually going to end up being ten, but yeah, that ballpark.

But usually, what we will be doing when we're not having an event like this... on a day-to-day basis... is receive calls from people who are actually requesting that we bail someone they know out... we'll look up their information, and if we have the funds to bail them out, we'll do so...

You asked about what people's responses were when we bailed them out, and obviously people were happy, they were delighted to be out of jail, they were grateful. Some people were just like 'Hey thanks so much, I'm out!' and then just beelined for the door because they've been inside and want to be outside, and because they don't know who we are...

There were also people who we gave rides to, had chats with, things like that. We did have literature that said a little bit about where we're coming from that we would hand to them, so that they can kind of digest it on their own time."

How does someone reach out to the bail fund for support?

Julie: "We have a phone number that people will be checking, so if someone call or texts the number you probably won't get an [immediate] response, or like – no one will pick up the phone, but you can leave a message... and someone will get back to you, ideally within 24 hours, to follow up on what your situation is, who you want to bail out, how much the bail is, etc. We'll just kind of follow up on next steps to coordinate when to post bail, when to have release support, and stuff like that. If we don't have the funds to post bail for you, we'll talk through what the options are.

That phone number is (828) 542-1312. And actually this is an interesting tidbit – we investigated a number where the last four digits would be 'BAIL,' so that it's easy to remember, but those phone numbers were extremely expensive because of this for-profit bail bonds industry which is extremely lucrative and predatory."

Is there anything else you'd like to share?

Julie: "Bail funds have always been important as long as the state is holding people for ransom... but it is very clear that at this time, and in this place, a community bail fund is a critical piece of community survival infrastructure... there are groups of people feeding folks, and there are groups of people who are resisting encampment sweeps, and the state is just so set on removing people to create a sanitized space for commercial activity, or just middle-class people's comfort... the same folks who are having their encampments swept day after day are getting messed with by the cops. So, that is just a cycle, and it's crazy that a bail fund would be just as important as food or shelter – but because food and shelter are so precarious for folks, that just [increases] the need for a community bail fund so much more, because the systems that should be supporting folks have been completely removed... so yeah, it really is all connected.

The other thing is... I've talked a lot about structural crises, but there is a reality of people doing immense amounts of harm to each other, and that shouldn't be made invisible. But the reality is that the bail system just has nothing to do with that. So people will say 'what if this person did this, or what if this person did that'... but there is just no reality in which it can be justified that X person who the state says did X thing can be free if they have money, but another person who the state says did the same thing can't be free if they don't have money... the whole concept of community safety is belied by the cash bail system.

So while we don't want to sweep under the rug or minimize the fact that like, yeah, people do harm each other. That's a real thing. But the cash bail system doesn't – in any way – help, heal, avoid, or address that. The things that will help, heal, avoid, or address that are a whole other set of practices of community care, which, again, are being broken down by the state."